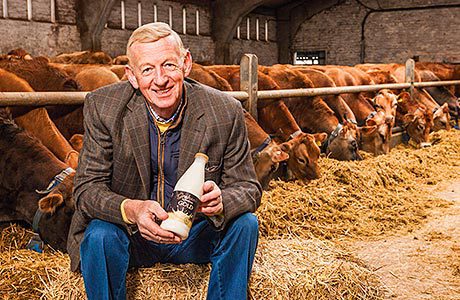

Dr Robert Graham on how he and his family’s company have grown up in the Scottish dairy scene

MILK from the Graham’s the Family Diary plant in the Stirlingshire town of Bridge of Allan goes into stores of all shapes and sizes throughout Britain, but it’s still processed at the farm where the company was born in 1939.

Dr Robert Graham – son of the founder and dad to the third generation of Grahams to work in the business, managing director Robert and marketing director Carol – was born on the farm too. He began working in the company “at a very early age” and though he handed over the MD reins to Robert in 1996 he’s still heavily involved, and perfectly positioned to talk about the company and its place in the dairy scene past, present and future.

“In the early days the cows were milked by hand and the milk was put into a churn and on to a pony and trap and taken to the village,” he said.

“Then there were a few more cows, the milk went into glass bottles and we moved into automatic milking around 1948. But up until the early 1960s it was raw milk, a premium type but unpasteurised.”

As the industry moved to pasteurisation it allowed milk processors and bottlers like Graham’s to sell to shops, a trend that intensified as women moved en masse into the workforce.

“More and more milk was going through the shops and when the supermarkets came along doorstep deliveries were just about destroyed, especially in Scotland,” he said.

By that time, the early 80s, Graham’s had well and truly moved into the modern world of milk but there was more to come.

As the 80s progressed the plant at Bridge of Allan was extended. The company is still a dairy farming concern but these days also has contracts with other farmers.

“They’ve all been personally chosen by me,” Dr Robert said. “They’re all good farmers, guys that do things well and are ready to invest.”

The 80s also saw the milk-drinking public become increasingly health-conscious. Equipment was installed that extracted cream and allowed the company to serve the growing demand for semi-skimmed milk.

And in the early 90s, looking for a way to make the best of the cream that was left over, Graham’s the Family Dairy entered the butter business.

“My mother had always made butter here on a small scale,” he said.

And the commercial version of Graham’s butter is designed to be very close to that domestic product from the early days of the dairy farm.

“Many companies who make butter buy it in from all over Europe, bring it to the UK, break it down, rework it and pack it,” Dr Robert said.

“We must be one of the few companies that makes it from the milk that comes into the dairy. It’s a churned butter made in the traditional way.”

The latest Kantar Worldpanel market research figures show it is the fastest growing butter in Scotland.

But, pleasing as the performance of the butter might be, if you really want to see Dr Robert’s eyes light up just get him to talk about the firm’s Jersey milk lines.

The firm produces premium Jersey milk and cream for its own range – products like Graham’s Gold – and for several of the supermarkets.

“It’s very popular, we can’t get enough,” he said.

“We’re short of Jersey milk just about every day.

“But, if you get the chance, try some Graham’s Gold on your porridge or cereal in the morning. It’s fantastic!”

The firm’s doing well but life hasn’t always been easy in the dairy industry. He notes the continuing milk price war in supermarkets and discounters and the pressure that can put on processors and farmers.

“It’s only in the last year or two that the farmers have been able to make some money. The previous bad summers had meant they had to import expensive feed and production costs went through the roof.”

He expects prices to be stable this year but is concerned that when EU milk quotas are done away with in 2015 there will be a glut of milk from other European countries like the Republic of Ireland.

Provenance, already a major part of the company’s marketing story will become still more important.

“Our main opposition is either Danish or German,” he said.

“We’re the only Scottish dairy company of size. We know all the farms that our milk comes from and we can follow our milk all the way to the customer.

“I think our Scottishness is important. I think people do support us because of it.”